As far as my musical life is concerned, everything has been turned on its ear. The band lost our secret weapon to health issues; my solo work guitarist joined a band; my new piano player and singing partner got called away to work on a Broadway album; so musically, I was a dead man walking during the holidays. Good news is the band has a new guitarist and vocalist, and our first official show with the new line-up is in two weeks, which just happens to be my annual Birthday Bash – I will have a Rock Star post about the bash soon after; and as soon as I’ve cleared the air with my two musicians, I’m hoping to have another post or two.

As far as my musical life is concerned, everything has been turned on its ear. The band lost our secret weapon to health issues; my solo work guitarist joined a band; my new piano player and singing partner got called away to work on a Broadway album; so musically, I was a dead man walking during the holidays. Good news is the band has a new guitarist and vocalist, and our first official show with the new line-up is in two weeks, which just happens to be my annual Birthday Bash – I will have a Rock Star post about the bash soon after; and as soon as I’ve cleared the air with my two musicians, I’m hoping to have another post or two.

In the meantime…

I wrote this over on Facebook, decided I needed to go ahead and share this here. Because even though this blog is supposed to be about me becoming a Rock Star, this is part of who I am, and a big reason I am who I am.

It is the 25th Anniversary of Desert Shield and Desert Storm. When I joined the Army, it was three weeks after the invasion of Kuwait. I did not join because I wanted to get shipped off to the Persian Gulf – I joined because my work life was going nowhere, I was in love with a wonderful woman I could not support, and I was desperate to feel that sense of belonging and purpose I had back when I’d been a kid in Boy Scouts and JROTC. I wanted to belong to something greater than myself… but I also didn’t want anyone asking me why I didn’t have the stones to go off and do my patriotic duty. So even though there was a very good chance I’d find myself in the middle of a desert in six months time, I signed the paperwork, took my oath, and headed off to Basic Training a month later, September 25th, 1990.

I got my orders to go to Desert Storm on February 1st, 1991; I got married on the 3rd, and then graduated on the 8th. I took a quick trip back to Texas so that everyone I cared about would have one last memory of me laughing and smiling; and then I flew back to Augusta, Georgia, where I would spend the next week doing… well, nothing. Somewhere deep inside the Pentagon, it was still being debated exactly how many troops would be necessary for the Persian Gulf; while the Generals and Admirals made up their minds, I spent a week picking up garbage, mowing grass, and trying to stay out from underfoot. Even after I was shipped down the road to Fort Benning to be outfitted, there was still scuttlebutt our particular group of soldiers wouldn’t be called on, more than enough boots were already on the ground. So while we took possession of our still-wet from gun oil M16A1’s and fresh, never-before-used protective masks complete with atropine injectors, the ones of us with something or someone to lose kept hoping and praying we’d get left behind.

February 19th all that hoping and praying were for nothing. We all loaded up onto a double-decker jumbo jet, wedging all our gear in around us, and took off. First for New York City for fueling and supplies; then to Belguim for more fuel and fresh pilots; and then finally to King Fahd International Airport in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. The trip took nearly twenty hours – even though we’d boarded around 6am, I stayed awake the entire flight. The last thing I wanted to do was rush this trip, so I did all I could to make the flight last as long as possible.

I’ve always had a high opinion of myself – I’m smart, talented, and semi-charming when I’m not trying too hard. I never thought I’d actually end up in a war zone – somehow, someway, the Universe would pull some strings at the last second, poke me in the ribs and exclaim “Psyche!” and put my butt somewhere else out of harm’s way. I was still holding on to that delusion five minutes before the jumbo jet landed – the pilot came over the loud speaker:

“This is your captain speaking. We’re coming up on King Fahd International Airport and are going to start our descent. Since we’re not sure what can of reception to expect, we’re going to corkscrew in so it’s harder to get a bead on us. If at any time I hear bullets bouncing off this aircraft, I will gun the engines and we will head back to Belgium. Attendants, prepare for final approach.”

Never before in my life had I ever prayed to be fired on – my prayers were not answered. Twenty minutes later, I was on the tarmac and carrying my gear towards an airplane hangar full of cots. And it hit me that I was not one of God’s favorites – I wasn’t going to get a last-second reprieve; I was going to war. Worse, I was no longer a person – I was just a thumbtack on a map signifying unit strength and placement. While I could say that I was truly a part of something bigger than myself for the first time in years, I’d done so by sacrificing my individuality. I was just a service number on someone’s clipboard somewhere, a faceless, nameless cog in the military machine. If I died, no one I cared about would know for months, maybe years.

(Maybe not at all. The Army had sent me overseas in such a rush, my records had become lost. I would be stateside six months before my records would catch up with me in Colorado.)

Since the 8th, every time I stepped onto a vehicle, some of the soldiers I knew and had trained with had been pealed away and sent somewhere else. Graduation had sent all the Reservists and Guardsman back to their homes, including my best friend and Best Man; the trip to Fort Benning had separated more of my old company; and after a night at the airport, the replacement detachment people divided up even more of my old squad. By the time I loaded up onto the old, rickety double-decker bus, I was by myself. No one I’d met in Basic Training was still with me. My support system was now the Army. I’d have to depend on the fact we were all in the same uniform to prompt my brothers and sisters to watch my back… just as they’d depend on their uniform to prompt me to watch theirs. Which is how my particular experiences differs from my contemporaries, my other friends around my age with military experience like my band leader – when they were sent into hairy situations, they were with the people they knew, soldiers they had trained with. They knew how each squad member would react in given situations, had some indication as to how their NCO’s and officers would lead them. I had none of that – all my friends, squad members, NCO’s and officers were gone. I was surrounded by hundreds of people wearing my uniform, and yet I was completely alone.

(Well… sort of wearing my uniform. While I had gotten a new rifle, bayonet, helmet, and protective mask, I had not been issued a Desert Camouflage Battle Dress Uniform – I was still wearing the Woodland Green BDU’s I gotten in AIT, the replacements for the set I’d been issued in Basic Training that no longer fit after I’d dropped forty pounds. The other soldiers that had been snatched up directly out of AIT were also in green BDU’s – the joke soon became if some sort of enemy aircraft came in for a strafing run, we should all huddle together and try to camouflage ourselves as an oasis.)

There is scared, and then there is scared… and then there is what I was experiencing. I was numb. It was as if someone had injected novocaine into my emotional core – I was thinking clearly, I knew exactly what was going on, I understood what was being explained to me and I followed orders to the letter… there was just no emotional response to any of it. I was scared past the point my system could process it, so it had stopped processing anything: no fear, no joy, no skepticism, no anger, no longing, no nothing. As far as emotions were concerned, I was a functioning corpse.

(While I was awake – asleep, I had nightmares of being chased by something horrible trying to kill me. One night it was Jason from the “Friday the 13th” series; the next night, it was the Alien aboard The Nostromo; zombies shambled after me one night; and one extra special night, it was the giant spider I’d first dreamed of when I was four years old, the jet-black horror the size of a VW Beetle that had haunted me ever since. Every night, I sat up, jolted awake by whatever it was pursuing me, trying to catch my breath and hoping I didn’t cry out in my sleep… only to realize I was in the Army, sleeping in the dirt with my field jacket as a pillow, in the middle of a war zone. And then I would wish I was still asleep – as terrible as the nightmare had been, it was less terrifying than the reality I was living.)

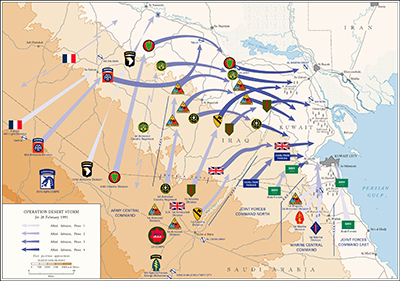

I was supposed to join an artillery unit that was laying down suppressing fire for the 101st, but my convoy got stuck waiting for a tank division to cross the one and only highway going our direction for four hours; by the time we reached the halfway station, it was after dark. Since it was pitch black and a wrong turn meant finding yourself inside the wrong end of Iraq, our bus driver refused to go any further – we’d carry on at first light. That night, February 22nd, the ground assault officially started; and by first light, the unit I was supposed to be joining was one hundred miles in country. The decision was made that I and the rest of the replacements would stay at the halfway station until our receiving units found a place to park.

I was supposed to join an artillery unit that was laying down suppressing fire for the 101st, but my convoy got stuck waiting for a tank division to cross the one and only highway going our direction for four hours; by the time we reached the halfway station, it was after dark. Since it was pitch black and a wrong turn meant finding yourself inside the wrong end of Iraq, our bus driver refused to go any further – we’d carry on at first light. That night, February 22nd, the ground assault officially started; and by first light, the unit I was supposed to be joining was one hundred miles in country. The decision was made that I and the rest of the replacements would stay at the halfway station until our receiving units found a place to park.

(Replacements. The military estimated that there would be 30,000 casualties the first wave of the ground assault, so all of the units had the number of their personnel increased to 125% capacity. I and the rest of the soldiers I was holed up with were to replace those unit members injured or killed during the first wave, which is why a communications graduate was being sent to an artillery unit.)

I don’t pray often. Not because I don’t think it works, but because of the exact opposite – I do think prayer works, and if a prayer of mine is to be answered, I want to make sure it’s a situation completely out of my realm of control, as close to a miracle as possible. It’s rare when I pray, but I found myself gazing into the heavens that night. That far out in the middle of nowhere, there are no ambient city lights to interfere, so stars are visible all across the sky. In all my years of Scouting and volunteering with The Order of The Arrow, I had never seen some many stars. I had listened to everything my drill sergeants had been telling me since late September, I knew what was expected and what had been planned for, and I knew what my chances were expected to be. I wasn’t scared of dying – when you’re dead, you’re dead, nothing left to worry about – but I couldn’t shake something one of our drill sergeants had said weeks earlier:

“It’s not the bullet that has your name on it you have to worry about – it’s going to find you no matter what – it’s the one labeled ‘To Whom It May Concern” you gotta look out for. ‘Cause it don’t care who or what it hits.”

I didn’t want to lose my legs. I didn’t want to end up blind. I didn’t want to be maimed. I didn’t know how strong I could be, and I didn’t want to put my wife of less than a month through a lifetime of nursing me. So I prayed. I asked whoever or whatever it was that had me convinced there was a higher power at work to not let me be crippled; if going home whole was not to be, then please, just go ahead and kill me.

I then told the Universe I’d make it easy. I had every intention of going home. I had a new wife I’d never been on a honeymoon with, never lived with as a married couple with, and I’d be damned if I didn’t get the chance of experiencing the simple joys with her. I was going home, so whatever and whoever got in-between me and her had to go. I’d kill whoever I needed to, I’d destroy whatever I needed to, I’d become whatever monster I needed to be to make that goal. I wasn’t asking forgiveness – I was just stating fact. If I wasn’t to go home, then kill me now, because there would be no middle ground.

Four days later, the cease-fire was called. The middle ground wouldn’t be necessary – I’d be going home. And well sooner than expected: mine had been one of the last planes to land before the ground assault, so I was with stationed with a bunch of Independent Ready Reservists who’d been called up with just days left on their contracts. The IRR’s had careers and families back in the States, and their wives were hard at work, calling their Congresspeople to get their husbands sent back home ricky-tick. Their combined pestering worked, so instead of the six months I’d expected to spend in the Persian Gulf, I spent just under six weeks, long enough to earn a couple of medals and the right to wear a combat patch.

After that, life happened so fast, I didn’t have a lot of time to process what I’d been through… other than to notice my head suddenly sparkled. Where once I’d had a stray silver hair here or there, I now had hundreds of stark white strands all over. I moved my wife to Colorado Springs for two years of active duty; then to Arlington, TX for three years of Reserves while I want to art school at night, holding down a full-time job during the day. It wasn’t until after I got my orders moving my status to the IRR and I graduated that the war began to seep in. Not showering enough love and praise on my deserving wife was the first indication something wasn’t completely up to snuff; a lingering dissatisfaction with my day job and it’s lack of social significance another. But it was after the invasion of Iraq that everything came bursting out.

9-11 had been traumatic, but no more so for me than it was for any other American; the invasion of Afghanistan didn’t bother me, really – if anything, I was disappointed it had taken weeks to get to doing what I thought would be undertaken the week after the Twin Towers came down; but when the military went into Iraq, something inside me snapped. Iraq had been my war, and my war had been over for a decade. I had gotten accustomed to my participation being overlooked or even forgotten… and yet, here it was: boots in Iraq, fighting my war all over again, restarting what I had been led to believe had been finished. As I watched the news, as I saw the troops land inside my war zone, I began to sniffle. Slow tears began to slide down my cheeks. I wiped my eyes and went back to getting ready for my day job, making pretty pictures to sell couches to the Middle class… only the tears kept coming. Not a sobbing fit… just slowly tearing up, clearing my throat and wiping me eyes, over and over and over again, for the next three days.

For three days, the only time I wasn’t crying was when I was asleep. I stayed home from work. The counselor I’d started seeing after my marriage had started to crumble was sympathetic, but not much help. If I wanted the tears to stop, I’d need to confront all the stuff I’d buried a decade earlier.

There’s an unspoken truth to being a soldier: you’re only truly a soldier when you’ve done your job during a war. Whatever you’re particular job specialty, part of what you train for, part of what you prepare for, is doing that job in the field during a combat operation. And while the training and preparation is vitally important, it is still not the real thing; soldiers with combat patches – sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously – get afforded a higher level of respect than soldiers without. I had a combat patch; I had felt that respect while I served; but I also felt like a fraud – I’d only done half my job. I knew what it was like to stand up and be counted, I knew what it was like to be ready to lay down my life, and I knew what it was like to be in a war zone surrounded by not just enemies, but FEAR… but I didn’t know what it was to be under fire; I didn’t know what it was like to be counted on to protect my brothers and sisters; I didn’t know what it was like to take another life in defense of everything I hold dear; and I especially didn’t know if my courage would hold true in the face of hopeless odds.

During the war, I’d been prepared to do terrible things – now, years later, part of me was thankful I’d never had to do those terrible things; but just as large a part of me was wracked with guilt I hadn’t done those terrible things. Thankful I hadn’t had to do a terrible job, but left feeling like a fake because I hadn’t had to do a terrible job. And now that ground forces were back in Iraq, I was thankful I wasn’t there with them, yet feeling guilty that I wasn’t still serving my country; and worse, even more guilty for feeling thankful it wasn’t me overseas a second time.

For years, my wife and I would see and read reports of people who’d never finished their military contracts finding themselves called back into uniform years later. People a hundred pounds overweight, grandmothers in their 50’s, high-paid executives who had forgotten to resign their commissions, all being backdoor-drafted back into serving. And even though I knew my contract was over, I’d received my letter saying I’d been removed from IRR roll, I still went to the mailbox every day with dread, half-expecting to find the letter commanding me to go to my nearest recruitment center, half-hoping to find that same letter so the dread and the guilt would finally be over.

I was at home, in-between freelance assignments, when the troops officially left Iraq a few years ago. I cried as I watched the convoy cross over the border. Since that day, I haven’t had a nightmare about being reenlisted in the Army – while there were still troops in Iraq, I had that nightmare every six to eight weeks or so.

It is the 25th Anniversary of Desert Shield and Desert Storm. It’s the middle of an election season, so the anniversary of the ground assault has been overlooked and ignored by the media except for the military magazines and newspapers. It originally took about two years for me to go from being an American hero to a footnote. Back in 1993-94, the economy was starting to improve, unemployment was dropping, and the stock market was beginning a meteoric rise. The Persian Gulf had been the former President’s war, and he was gone, replaced by charismatic Southerner who had never served in uniform. No one was still itching to shake the hand of a veteran any more – they all had important things to do.

After the caskets started coming back week after week, month after month, after “Mission Accomplished” had been declared, suddenly the same folks who’d had important things to do ten years earlier were crying as they hugged me, thanking me for my service. by 2006, I was back to being an American hero again.

Another ten years have passed, and I’m back to being a footnote. The veterans of Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom are probably starting to experience that sensation, as well. No one is talking about the “advisors” that are still in Iraq and Afghanistan, no one is talking about the backlogs in the VA hospitals, and no one is talking about the suicide rate among the recently discharged veterans.

It is the 25th Anniversary of Desert Shield and Desert Storm. Since mid-January, when I haven’t thought about my 50th birthday party bash in March, I’ve looked at the calendar and remembered where I was 25 years ago. This isn’t just my 25th Wedding Anniversary, and this isn’t just my 50th birthday… this is the 25th anniversary of my becoming a Desert Storm veteran, and like it or not, that is just as important as the other two events. I’d be lying if I said there were never times I wished that wasn’t the case… but it is what it is. And I am who I am.